EGOS subtheme 2021

Justifications for organizing an inclusive society

Dirk Lindebaum

Grenoble Ecole de Management, France

Ismael Al-Amoudi

Grenoble Ecole de Management, France

Jean-Pascal Gond

Cass Business School

City, University of London, UK

To most things we do, there is a justification—conscious or otherwise. When we make decisions, principles of accountability and transparency impel us to offer a justification as to why we decided this rather than that. In our ‘audit society’ (Power, 2000), managerial and organizational activities involve continuously the use of justifications, or ascertaining “a good reason or explanation for something” (Online Cambridge Dictionary).

This proposed subtheme seeks to broaden and explore the concept of justifications to better understand how we can organize ourselves for a (more) inclusive society (i.e., a society that embraces equality and respect for diversity as an antidote to waning solidarity). For Forst (2017: 34), justifications, and the orders of justifications that they add up to over time, are foundational for social reality. In his words, “every social order must be conceived as an order of justification [that] consists of a complex web of different justifications”. His thinking aligns thus with the work of Boltanski and Thévenot (2006: 37), who see an ‘imperative to justify’ as central to maintain collective action despite disputes, or Berger and Luckmann (1966: 93), who underline ‘legitimation’ and ‘justifications’ as central elements in the construction of social reality.

In light of these conceptualizations, justification is by essence a political process, since it shapes the interpretational sovereignty of whose reality is valid, or whose reality matters more than that of others. Further to this, justifications help explain ethical or moral norms, or concepts of the ‘common good’, and actively shape what kind of future it will be worth having (e.g., creating a more just society by exposing patterns of domination and exploitation (Scherer, 2009). At the same time, they can be misused to turn evidence-based policies into policy-based evidence (e.g., political debates around Brexit, where facts seem to matter less, or climate-scepticism).

Given the ubiquity of justifications in the construction of social reality, this ‘meta-theme’ impinges upon a variety of topics that are of intrinsic interest to organisational theory, such as power and control (Al-Amoudi & Latsis, 2014; Gond, Barin Cruz, Raufflet, & Charron, 2016), fake news, ‘alternative facts’ and conspiracy theories (Knight & Tsoukas, 2019; Schreven, 2018), normative theorizing (Lindebaum & Gabriel, 2016; Suddaby, 2014), rationality and decision-making (Lindebaum, Vesa, & den Hond, 2020), and choices of paradigms and methods (Guba & Lincoln, 1994), to name only a few.

It is against this background, and irrespective of theoretical or methodological traditions, that we invite submissions that address a range of indicative but not exhaustive themes:

Unpacking organizational and material dynamics of justification

- While organizational studies of the ‘economies of worth’ (EW) provide a conceptual grammar of normative principles referred to as distinct ‘worlds’, scholars have not yet fully analysed the foundation of organizational heterarchy (Stark, 2009), nor unpacked the mechanisms underlying multiple forms of justification within each world (e.g., distinct forms of worth in the green or market world). What insights can be gained by probing deeper into the each ‘world’ through the ‘Five Whys’ test (Serrat, 2017)? Can we distinguish distinct dynamics of justification within each world?

- Can we cross-fertilize analytically distinct conceptualizations of justification to unpack further the moral foundations of organizational dynamics of justification?

- What is the role of material artefacts in justification dynamics? Do they operate mainly through ‘tests of worth’, or can they play a more agentic role in justification dynamics? How can technology contribute to establish and challenge moral justifications, especially when its design to ‘bring things to people’ rather than ‘bring people to things’ implies abject and immoral decisions (Lindebaum et al., 2020)?

Organizing for the common good through justification

- If an inclusive society and/or the pursued of the common good is the goal, how can justification frameworks help us understand how multiple visions of the common good compete, interact or are dynamically organized and combined? How and why can the dominance of one world marginalise others, and how can marginalisation be reversed? How can dominant (im)moral orders be subverted?

- What is the potential of theories of moral development to enrich the existing literature on EW on their cognitive side, given that the former is concerned with the principles (and hence justifications) through which to achieve justice? Reciprocally, can the focus of the EW on the multiple forms of common goods help enrich theories of justice and fairness in the workplace? What is the role of justification in individual and organizational processes of ethical decision making?

Exploring how power plays through (and without) justification

- With a nod to Lenin’s famously stated power question ‘who whom?’, how can justifications be (i) (ab)used by powerful individuals or organisations to get away with saying what about whom, and to (ii) decide “who is in a position to stop other people saying what about them” (Garton Ash, 2016: 292)?

- What is the role of secrecy and unobtrusive power so that power can escape justifications?

- What are the causes and processes through which one world (e.g., the industrial world) becomes more dominant than others (e.g., inspired world)? Do higher orders of worlds imply ‘hierarchy’ of worlds?

Approaching justifications as epistemological devices

- Since paradigms represent basic belief systems that “must be accepted simply on faith” (Guba & Lincoln, 1994: 107), what measures can be envisaged to hone the justification underlying paradigmatic choices, and how that enables the approximation of truthfulness?

- What can American pragmatism (e.g., Wright Mills, 1940) teach us about justification dynamics?

- What role do justifications play as methodological, epistemological and/or pedagogical tools to produce, transfer or translate knowledge (e.g., rigour vs relevance debate?)

References

Al-Amoudi, I., & Latsis, J. 2014. The arbitrariness and normativity of social conventions. The British Journal of Sociology, 65(2): 358-378.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality. New York: Doubleday.

Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. 2006. On Justification: Economies of Worth. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Forst, R. 2017. Normativity and Power: Analyzing Social Orders of Justification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garton Ash, T. 2016. Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World. London: Atlantic Books.

Gond, J.-P., Barin Cruz, L., Raufflet, E., & Charron, M. 2016. To Frack or Not to Frack? The Interaction of Justification and Power in a Sustainability Controversy. Journal of Management Studies, 53(3): 330-363.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. 1994. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research: 105-117. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Knight, E., & Tsoukas, H. 2019. When Fiction Trumps Truth: What ‘post-truth’ and ‘alternative facts’ mean for management studies. Organization Studies, 40(2): 183-197.

Lindebaum, D., & Gabriel, Y. 2016. Anger and Organization Studies – From Social Disorder to Moral Order. Organization Studies, 37(7): 903-918.

Lindebaum, D., Vesa, M., & den Hond, F. 2020. Insights from ‘The Machine Stops’ to better understand rational assumptions in algorithmic decision-making and its implications for organizations. Academy of Management Review, 45(1): 247-263.

Power, M. (2000), The Audit Society — Second Thoughts. International Journal of Auditing, 4: 111-119.

Scherer, A. G. 2009. Critical Theory and its Contribution to Critical Management Studies. In M. Alvesson, T. Bridgman, & H. Willmott (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of critical management studies: 29–51. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schreven, S. 2018. Conspiracy Theorists and Organization Studies. Organization Studies, 39(10): 1473-1488.

Serrat, O. 2017. The Five Whys Technique, Knowledge Solutions: Tools, Methods, and Approaches to Drive Organizational Performance: 307-310. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

Stark, D. C. 2009. The Sense of Dissonance: Accounts of Worth in Economic Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Suddaby, R. 2014. Editor’s Comments: Why Theory? Academy of Management Review, 39(4): 407-411.

Wright Mills, C. 1940. Situated Actions and Vocabularies of Motive. American Sociological Review, 5(6): 904-913.

Convenor Biographies

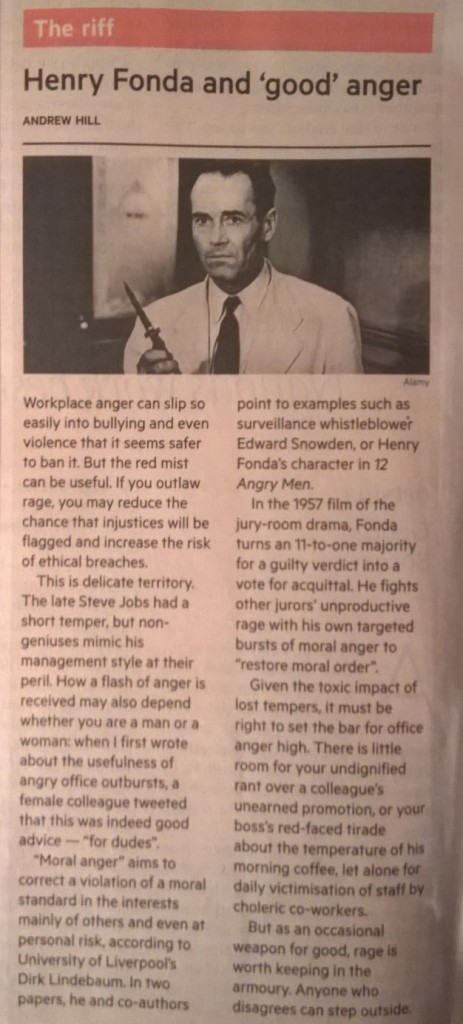

Dirk Lindebaum is Professor in Organisation & Management at Grenoble Ecole de Management (France). Favouring the pursuit of ideas over disciplinary boundaries, his research seeks to understand the mechanisms through which we lose (and can regain) freedom at work, be it through emotional or technological means. His work regularly appears in news outlets, such as Financial Times, New York Times, BBC Radio 5 Live, Wirtschaftswoche, Independent, Fortune Magazine and Bloomberg Business Week, to name only a few. For more information, please visit his website: https://dirklindebaum.EU

Ismael Al-Amoudi (Phd, University of Cambridge) is Professor of organisational theory at Grenoble Ecole de Management. He is also the Director of the Centre for Social Ontology and an Associate Editor of Organization. Ismael’s research stands at the intersection of social theory, ethics and management studies. He is particularly interested in how social norms are justified and transgressed, and how norms matter to people’s powers, sense of worth and identity. Recent publications include papers in Academy of Management Learning & Education; British Journal of Sociology; Business Ethics Quarterly; Cambridge Journal of Economics; Human Relations; Organization; and Organization Studies.

Jean-Pascal Gond is Chair Professor of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) at Cass Business School, City University London, UK. His research, which investigates the social construction of CSR and the performativity of management theories, has been published in journals such as Academy of Management Review, Business Ethics Quarterly, Organization Science, Organization Studies, Journal of Management or the Journal of Management Studies. Jean-Pascal Gond is member of EGOS since 2003 and has attended all the EGOS conferences since then, including as sub-theme convenor over several years.